Enigmatic data from an enigmatic country

Denmark is in the headlines for all the wrong reasons. Once a pioneer of shared parenting recent reports from Copenhagen indicates that the government is about to select a reverse gear – to flip flop, as the Americans might say.

It was the Copenhagen Post of Feb 13th 2012 that set the cat among the pigeons with the predictive headline “Parliament to end 50-50 child custody rule.” If true this would represent a symbolic setback to campaigners worldwide who have promoted shared parenting.

In the article Jennifer Buley wrote:

- “In a unanimous decision, the political parties agreed last week on a plan to change the national child custody laws, abolishing the default 50-50 shared custody arrangement for the children of divorced parents.”

The story went on to say how Danish MPs acknowledge:

- “. . . that forced co-operation and shared custody do not work for all divorced families . . [leaving]. . . politicians to rethink law.”

And as if to justify the change MPs reportedly took the view that;

- “. . . the new law will put more focus on the rights of children as opposed to the parents.”

Sadly, this journalistic shorthand veils the fact that Danish courts are not mandated to automatically give 50-50 custody in all cases. No one would want any particular style of custody “forced” onto divorced parents be is sole custody or shared custody if it was not appropriate and mutually agreeable. So far the world has had to live with sole mother custody forced upon it and it has proven to be unpalatable. Equally, we should expect the same disagreeability when shared custody / shared parenting is mandated in every case.

But is that really the case ? One look at the 2007 Act tells you it is not.

Denmark’s strides towards universal shared parenting culminated in the Parental Responsibility Act 2007, (Act No. 499), which has since been amended in 2009. [1] This Act does not force shared parenting or joint parenting on any couple. It allows for ‘contact’ and ‘residence’ in the normal way. It allows for sole custody as well as joint, so on the face of it there is nothing mandatory about it.

Chapter 3 Para § 17 clearly states that:

- If the parents have joint custody, and they do not agree with which of them the child shall reside, this determined by the court. The court may decide that the child can live with a parent who has or wants to live abroad or in Greenland or the Faroe Islands.

A second paragraph in Chapter 3 adds that another court may modify an agreement or decision regarding the child’s residence – so it’s not as if things are set in concrete at the first court.

Furthermore, the 2009 amendments to the 2007 Act incorporate this clause Chapter 1, Sects 11. 2 sections:

- “The court may terminate joint custody if there is evidence to suggest that parents can not cooperate in the child’s relationship to the child.” [2]

This builds upon the 2007 Act which calla for both parents to agree (and show) that they can operate joint custody or joint parental responsibility.

The Forældreansvarslov 2007 (Parental Responsibility Act 2007), was meant to address the ‘Dad deficit’ in post-divorce scenarios. The law was meant to maintain optimal connections with their children; however, critics now claim that “in practice it exposes the children to on-going conflicts and undue stress.” [3]

If this claim sounds familiar, it is. It is the universally scripted criticism voiced by opponents in many countries trying to introduce shared parenting.

Plot thickens

Not only was the 2007 Act passed unanimously by parliament but so too was its successor which allegedly curtails many of its provisions. To date Denmark’s parliamentary discussions seem impenetrable to my endeavours.

It is clear from the Copenhagan Post that Karen Hækkerup MP (born 1974), the Social and Immigration minister, and a member of the Social Democrat Party is tightly bound up with the most recent changes.

It is clear from the Copenhagan Post that Karen Hækkerup MP (born 1974), the Social and Immigration minister, and a member of the Social Democrat Party is tightly bound up with the most recent changes.

Left: Karen Hækkerup MP

The Copenhagen Post states that Hækkerup has spearheaded the negotiations to change the law (citing the Ritzau news service).

According to the same Copenhagen Post story of Feb 2012, parental responsibility was introduced (in 2007) to force co-operation and 50-50 shared custody the default decision in all child custody cases where parents could not agree on an alternative arrangement (and where both parents are deemed responsible).

The law envisaged each parent having custody on alternating weeks but having read the English translation this subtlety of interpretation appears to be one of several missing.

- “While it was intended as a fairer solution than earlier custody practices which typically favoured the custody rights of the mother over the father, forced shared custody has proven problematic – particularly because it has been applied to divorced couples who cannot agree on an alternative arrangement. The state and courts have insisted that they co-operate with one another, exchanging the children every seven days.”

This admission in the quote above undermines all the protestations heard in the rest of Western Europe and the Americas that fathers are not discriminated against in custody matters.

Hækkerup’s list of comments make interesting reading:

- “Parents who cannot co-operate and who are fighting a lot will no longer necessarily be forced to share custody of their children.”

- “Some people have used the parental responsibility act as a springboard for lodging one case after another. As soon as the one case about time-sharing or the child’s living arrangement is finished on a Monday, they file a new one on Tuesday.”

In the future, the state’s administrative arm, the Statsforvaltningen, will determine whether a situation has changed enough to justify a renewed custody suit (arrangement ?).  If the administration determines that it has not, and that the suit is not in the child’s best interest, the administration will be allowed to throw it out.

If the administration determines that it has not, and that the suit is not in the child’s best interest, the administration will be allowed to throw it out.

“We are making sure that the law will protect the interests of the children to a much greater degree than before,” added Hækkerup(http://statsforvaltning.dk/site.aspx?p=6398). However, and albeit from a sample of less than half a dozen articles, in Danish, the subtext for reversing the policy appears the old chestnut of fear of domestic violence playing a greater or lesser role in the rethink.

Denmark is a country of only 5 million men, women and children and so it does make one wonder just how many ‘awkward’ parents or high conflict families there are to constitute so fundamental a change.

In any given year there are around 15,000 divorces. Is the supposition that 50% of them are destructive, awkward parents from high conflict families or only 5% ?

Who bears responsibility ?

The development of Danish custody law was examined quite recently soon after the 2007 changes. In a 2009 article the peripheral figure of Christina Jeppesen de Boer, who has both Dutch and Danish family law links first appears (http://fkce.wordpress.com/2009/11/21/18/).

In the run up to the 2007 changes, it was envisaged that the new law might bring more cases to court because fathers stood a better chance of shared custody. These cases would be localised to those where one or both of the parents disagreed on custody and residence.

It was predicted that the new 2007 law on Parental Responsibility would work in the following manner:-

- Courts can, if they chose, impose ‘joint custody’ against the will of one or both parents.

- Administration by the State means that the courts can decide on 7-7 sharing arrangements where children reside equally with their parents (presumably, 7 days with one parent and 7 days with the other, and ditto for fortnight and monthly periods, presumably).

- There will no longer be a ‘proper age’ for consulting with the children of the union (presumably both spousal and cohabitee ?). This has formerly governed matters in relation to visitation (contact) and residence.

- In practice, children as young as 7 years will now be heard, to illustrate what the law calls the child’s perspective (see tender years doctrine).

In their ‘National Report: Denmark’, Ingrid Lund-Andersen & Christina Gyldenløve Jeppesen de Boer reinforce many points first highlighted in the “fkce” blog article.

Firstly, an interpretation of the UN’s Children Convention, is that the children’s perspective should be taken into account in divorce cases.

Secondly, the difference between the UN’s Children Convention and Danish law is that in Denmark the children’s statement, ie decision, has decisive weight. In the case of Denmark, this looked at the time as if the child had to understand that their evidence was crucial to the outcome to the custody case.

That burden and responsibility was adjudged greatly unfair for a child to bear by some – to say nothing about whether a child is competent to make a judgement that should take into account “outcomes”. This was at a time when Britain was moving away from putting the stress of decision-making onto children.

Judgement of Solomon

Many, including the authors Lund-Andersen & Jeppesen de Boer, believe children might be driven by a need to seek instant ‘peace’; to end the uncertainty and an immediate resolution by pointing to one particular model, say, mother custody, which after three weeks may realise may not necessarily work as they expected.

But, so the criticism runs, in the Danish system there is no room for mistakes – even if you are just seven years old.

At the time of the 2007 changes, Anette Hummelshøj, head of the Department of Family Affairs, admitted the new law could place an additional strain on the legal system:

- “But our expectation is that when the courts have established a clear line for the legal area, a higher number of parents will be able to settle either inside or outside the courts.”

The question is whether the surge in the number of conflicting cases re: both visitation and custody, is not really one of paperwork and begs the question that there is a need and room for improvement of the law.

Another question is whether or not the involvement of children in these cases could have the character of more listening and less questioning, so that children were spared the Judgement of Solomon responsibility that few adults experiences today.

Evolution in custody

The development of Danish custody law is as ’layered’ as most other countries. Whereas Britain didn’t get a Law Commission until the 1960s, Denmark had already set one up in 1910. It worked in close collaboration with similar Law Commission established in Norway and Sweden and the first Tangible changes came in a 1922 Act.

1922 Act– Prior to this Act the father, or more specifically the husband, was in a superior position in relation to his children, ie guardianship. In the case of divorce (rare in those days) parental authority, ie guardianship, appears to have remained with the father or was granted to one of the parents solely.

After 1922 the father no longer enjoyed a superior status. Custody was granted to only one of the parents with the primary criterion being given as the “child’s well being” (so that excuse / ruse / claim has a long pedigree). The main feature of the 1922 Act was that spouses were bestowed with joint parental authority.

However, the 1922 Act contained provisions regarding parental authority and ‘contact.’ The parent who was not given parental authority had a right to contact. One can speculate that this was the model adopted by other nations and ultimately by the EU and ECHR.

Only where both parents were equally capable of raising the child was a fault criterion used in order to give parental authority to the parent who was not to blame for the break-up of the marriage [italics added]. This mimics the priorities of the pre 1969 Divorce Reform Act in Britain.

Illegitimacy – For children born outside of marriage, the situation remained the same as before the law reform; the mother had full parental authority while the father had no right to contact (the same scenario as in Britain). As late as 1964 the Danish Supreme Court confirmed the difficult position of the unmarried father. It was established that, regardless of the circumstances and the father’s connection with the child, the father was not granted any contact rights with his child against the mother’s wishes

1960s – At the end of the 1960s and in the 1970s three changes to the 1922 Act were designed to give unmarried fathers better rights. In 1969 it was possible for an unmarried father to obtain a contact order. The conditions were that this was demonstrably beneficial for the child and took into account the child’s well-being; special circumstances; the father’s prior contact with the child.

1972 – By 1972 an unmarried father could obtain parental parental authority if the mother had consented to give the child up for adoption, but again only if pre-conditions could be met, namely of demonstrable benefit for the child; the child’s well-being; special circumstances; the father’s prior contact with the child.

1978 – At the close of the decade there was another “significant improvement for the unmarried fathers” (but so far no mention of up-grades for divorced fathers). It became possible in 1978 to transfer parental authority to the father, where this was necessary for the well-being of the child (one wonders how frequently this must have not occurred).

1986 – The Law Commission thoroughly revised the 1922 Act and wrote a report the main feature of which was a recommendation that joint parental authority be possible after divorce and the right extended to unmarried parents. The underlying reason for the change was that‘joint parental authority’ after divorce was becoming more popular in other Scandinavian countries and the US (though one wonders which US states they looked at in 1986 and what their definition could be for joint parental authority ?).

NB. Shadowing these developments in 1987 Britain saw the first judicial survey by the Law Commission into how many joint custody awards were being made in Britain as they has absolutely no idea at the time. If we are to believe Whitehall’s interpretation of those 1986 – 89 events joint parental authority was never considered an option in the UK – which is stretching credulity.

In Denmark it was thought that joint parental authority improved co-operation between parents and enhanced the sense of responsibility as far as parents were concerned. In addition, a universal right of contact for all parents was introduced.

Finally – and this bears directly on the above sections of “Who bears responsibility ?” and “Judgement of Solomon” – the opinion of a child if aged twelve or more was to be obtained before making a custody decision. For this task the authorities now had to offer counselling services when there was a disagreement on custody issues, i.e. parental authority and contact.

1996 – Another Law Commission report ushered in more changes. This time the provisions related to parental authority and contact and dealt with separately in Danish ‘Parental Authority and Contact Act’ (Lov om forældremyndighed og samvær). Again it was the unmarried father who had his position strengthened in terms of ‘parental authority’ the right to have contact with his child, as well as “other” contact rights such as the exchange of letters and improved rights to counselling.

2002 – Amendments to the Danish ‘Children Act’ of that year included maternity and paternity determination which had implications for the rules governing parental authority. A statement made by the parents to the effect that they would care for and be responsible for their child before or at the time of birth established paternity. When such a statement was made the unmarried parent automatically have joint parental authority. The procedure was not limited to cohabitating unmarried parents. From this we can deduce that a married and then divorced father had enjoyed ‘joint parental authority’ throughout this period.

At the same time a change was made to the effect that it was no longer required, as a formal part of the divorce proceedings, to make a decision regarding parental authority over the children.

Joint parental authority would be automatically assumed. The reasoning resulting from a suggestion by the Justice Department with the

2007 – The Parental Responsibility Act of June 2007 (Act No. 499), brings us to the current situation which is under threat of change. This Act underwent modifications in 2009 and 2010. The 2010 change allowed courts to terminate joint custody if it felt it suitable. That being the case one is left looking for the reason for reported wholesale change as proposed in 2012 media reports.

Statistical background

“Danmarks Statistik”, the official source of government statistics in Denmark does not have a wide selection of data and much is not in English. However, they have supplied what is pertinent (and current) to this present debate in the form of “5 pct. af de 1-2-åriges fædre har ikke forældremyndighed” which rougly translates as “5% – the fathers who have no parental responsibility [custody] over their 1 -2-year-old children.”

The following translation is the best that could be achieved given that some Danish words, e.g. dremyndigheden, do not have any English equivalent so any errors are due to that and my lack of skills.

However, before delving onto this specific area an overall appreciation of the basic marital data in Denmark might be useful.

“5 per cent. the 1-2-year-olds fathers have no parental responsibility” [custody]

(Google translation)

For every 1,000 children aged 1 and 2 years old, there were 47 fathers who did not have custody. The figure is slightly higher for the 0-year olds, namely, 66 out of 1,000 children. This variation may be due to the father’s parental responsibility being ‘detected’ by statistics (or acknowledged by the authorities) later than the mother especially when the parents were not married.

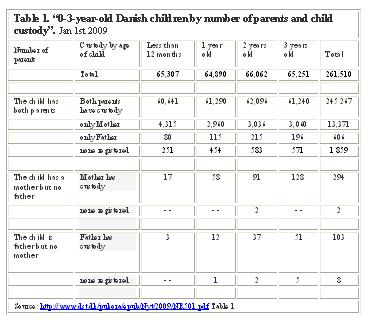

Most Danish children have both their parents, and parents share parental dremyndigheden [responsibility ?] in 938 out of 1,000 children aged between less than 12 months and 3 years (0 – 3 years). When only one parent is registered as having custody, it is usually the mother.

The information comes from completely new statistics. From the middle of 2004, the authorities started to register forældremyndighedsindehavere [to have custody of, or over] in the central register (CPR) for all children. By Jan 1st 2009 information on parental responsibility for almost all children aged between 0 – 3-year-old had been registered However, the data for older children is “incomplete”, ie ufuldstændige.

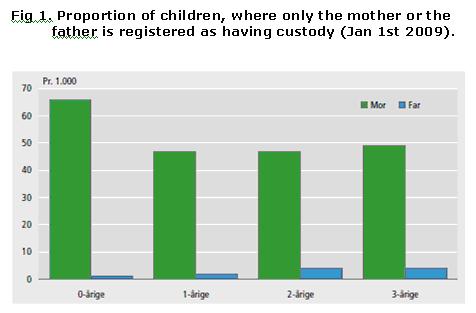

Figure 1. Proportion of children, where only the mother or the father is registered as having custody (Jan 1st 2009).

Numerically, only a few fathers are registered as having custody of their children. The figures are about 1 in 1,000 in the younger than 12 months old category, rising to 4 out of 1,000 for 3-year-olds. In the table above ‘arige’ translated to ‘years old’ and the green columns represent mothers with fathers shown in blue.

The netted down figures which excludes widowers, ie , where the mother is dead, 606 children are in the custody of their fathers. On the obverse, there were 13,371 children, where the mother had sole parental authority.

The starting point is joint custody

During 2008, there were 66,000 registrations of mothers and 63,000 fathers of custody for the 0-3-year-olds (see Table 2 below). The vast majority are records related to childbirth. Basically, parents have joint custody and both parents are recorded as joint authority holders.

In case of disagreement the matter may be divided by the state administration (statsforvaltningen), or by a court. Therefore, the parental authority records made by these authorities is seen as an expression of where there has been disagreement between the parents. Only a small proportion of all joint authority custody registrations happen to fall into the disagreement category and have to be dealt with by the civil service or the courts.

In 2008, the state administration authorities registered 2,131 parents, representing 1.6% of all custody records for the 0-3-year-olds. [One supposes this represents parents who could not agree – RW]. Of these 99% related to the father’s custody and only 1 per cent. mother.

According to “Danmarks Statistik,” this distribution is a result of the mother in almost all cases having custody of the child’s birth registration..

Courts registered 174 parental authority (parental responsibility) orders, equivalent to 0.1% of all parental authority registrations. Again, the majority – 139 records – were for father’s seeking parental responsibility.

E N D

[1] Forældreansvarslov 2007 (Eng eqiv. Parental Responsibility Act 2007).

[2] The Parental Responsibility Act, Act No. 499 of 6 June 2007, as amended by § 4 of Act No. 349 of 6 May 2009, § 3 of Act No. 494 of 12 June 2009 and § 3 of Act No. 628 of 11 June 2010, is amended. https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=142319

Pablo Piriz

October 26, 2012

Hi, I am a father from Uruguay, and my son is danish. I am trying to establish a visitation regime, and there is a disagreement with the mother, who believes than this is not relevant for de child. The espectation is, so far, than never my son is going to travel to Uruguay, and meet with his Uruguayan family. I can travel, but this is largely not enough, ¿can you give me some widelines? Thanks

Pablo

PLease answer by e-mail.

rwhiston

January 2, 2013

Pablo, I passed your details/request onto someone in Europe – have they been in touch with you ?

rwhiston

March 5, 2014

To my surprise I found Danish is more difficult to translate into English than German. Patter you might think is a derivative/corruption of Vader, Vater or latin Patris or Pater – but in Danish it means a teat, I believe.

aga

May 23, 2014

i am father from pakistan and i have two daughters in denmark my wife broke with me its one year and i also lost contact with my two daughters. and now case is in court but immigration office refuse my visa . does that mean i will not see my daughters again , i left denmark when i broke with my wife and now in pakistan

rwhiston

May 23, 2014

Dear Aga, You need the help of a Denmark-based father’s organisation to help you through this minefield. This is what the EU terms a ‘cross-border’ child custody issue. There is one formula/process for EU countries and another for no-EU countries. You do not say what sort of visa you have applied for ? The problem with Pakistan – and much of Arabia – is that they do not respect the rights of the other parent (Japan is the same). So the fear is of abduction with little or no chance of return to the other parent in the EU.

mission40kgsuraiya

August 26, 2014

we are law firm working with family law especially for foreigners . Is it Ok to write the name and contact details of the firm here?

mission40kgsuraiya

August 26, 2014

you can contact our law firm for family cases

rwhiston

August 27, 2014

Yes, of course, you are welcome to do that.

Please also list any special services and features available.

Casper

June 29, 2015

Hi I am from Pakistan, my wife Pakistani national but pr of Denmark availed divorce decree fraudulently in 2008, I was deported in 2007 due to.over stay, since then I have not seen my two children now aged 14 and 12, my wife is now imprisoned in murder of a man, i.applied for transfer of custody, but my children don’t want to come to Pak, I applied visa for court hearing but it was rejected, is there any chances to get back children? Please let me.know

rwhiston

June 30, 2015

I suggest you contact Men’s Aid – they might be able to help: National Helpline: 0871 – 223 – 9986

e-mail Help@MensAid.Co.Uk

rwhiston

November 24, 2013

Dear Francis, Your reply is ambiguous. Chuntering on about ‘patter’ helps us not one jot. Do you have practical experience of the Danish system ? Did it not work well for you ? These are the sorts of question we all would like to know and hear of your experience as the inference is that your know something of the system that we don’t. Is that a correct assumption ? We look forward to your contribution.

Francis Roy

March 3, 2014

I was looking though the statistics and found this referring link. There’s been a misunderstanding. I had written a post that was critical of a video, and had pointed to this page for statistics that were more accurate than what was presented in the video. The link that you see is a trackback link, that is, the blogging system is simply alerting you to the fact that a page on someone’s blog pointed to you. The text seen is an excerpt of the X closest words to the link. “Patter” referred to the patter in the video, not of this page. I was not engaging in this particular discussion. Hope this helps.

rwhiston

March 3, 2014

I see, I thought ‘Patter’ was a Danish term but you are using it in it colloquial setting of rapid speech / chatter.

I would just add that the Canadians have this same ‘equal but not not eual’ in their post Trudeau Charter. AS for England the Equal Rights laws etc make women equal to men but say nothing about making men equal to women where women have the advantage.

Francis Roy

March 4, 2014

“I see, I thought ‘Patter’ was a Danish term but you are using it in it colloquial setting of rapid speech / chatter.”

Yes, that is correct. Now I’m curious. What is the meaning of the term “patter” in Danish? I’m guessing that it isn’t a complimentary term. If so, I can understand that one might be annoyed! 🙂 It is a comedy of errors.

“I would just add that the Canadians have this same ‘equal but not not eual’ in their post Trudeau Charter. AS for England the Equal Rights laws etc make women equal to men but say nothing about making men equal to women where women have the advantage.”

As for Canada, I agree. Equality as lip service only. There is a very simple and important distinction to be made. Spread this one far and wide:

There is a distinction between “equal TO” and “equal WITH”.